Born in Hungary, fighting out of England, exiled to Australia, Joe Bugner was a man for all seasons.

The career of the former heavyweight contender makes for a fascinating study.

He bridged eras, fought big names, caused controversy, won fights he was expected to lose and lost fights he was expected to win.

He beat some damn good fighters.

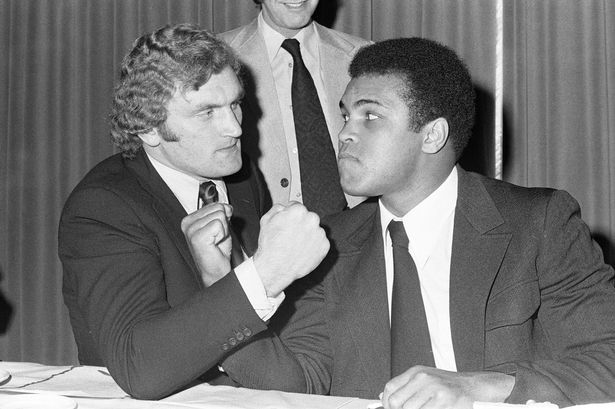

His list of opponents included Muhammad Ali (twice), Joe Frazier, Brian London, Henry Cooper, Juergen Blin, Mac Foster, Jimmy Ellis, Ron Lyle, Earnie Shavers, Marvis Frazier, James Tillis, David Bey, Greg Page, Frank Bruno, Scott Welch and Bonecrusher Smith.

His 32-year career resulted in a 69-13-1 (41 KOs) record, and when he called me at the Boxing News’ office in 2011 for a long interview, much of what we discussed was the fallout from his controversial win in 19791 over English darling Cooper.

Bugner won by ¼ point on the old system. Referee Harry Gibbs was the sole arbiter, but Cooper – in a fight for the British, Commonwealth and European belts – cried robbery, and did so for the decades that followed.

In a similar fashion to how Marvin Hagler stormed from the sport after his loss to Sugar Ray Leonard, Cooper also never boxed again.

“Look, after the Cooper fight nothing I did was good enough,” Bugner told me. “When I fought Frazier, Ali and beat most of the so-called top heavyweights in the world nothing mattered. I was just crucified for everything I did. [They’d say] ‘I fought like a robot.’ ‘I was so stiff.’ ‘I couldn’t do this and I couldn’t do that,’ and I said to myself, ‘Do I have to live with this crap?’”

The merciless British press didn’t cut him any slack, and he moved to Beverly Hills in 1975, and Australia in 1984.

Down Under, he became known as “Aussie Joe.”

He was just 21 when he fought Cooper and he was unable to shake the stigma that came as a result.

Bugner maintained that Cooper was simply too small as a heavyweight to make a difference, but added: “He left a legacy so no boxer in Britain will ever be able to walk in his shoes or his shadow. End of story.”

Cooper thought to his dying day he’d beaten Bugner, and it meant their complex relationship remained one of love and hate.

Bugner insisted that his team offered them a rematch with winner-takes-all stakes, but that was rejected, and Joe also said – behind decking Ali with his famous left hook – losing to Bugner was actually the second-best thing that happened to Cooper as it solidified his position in the hearts of the British public.

“Afterwards I walked back to the corner expecting Cooper, because of who he was and what he represented, to have his hand raised,” Bugner said. “I couldn’t have given a shit. But the Brits made it into a fiasco where they virtually chased me out of my beautiful country, which I loved very much and do to this day.”

Bugner also reckoned Cooper was playing a role, maintaining interest in the rivalry and himself once he’d walked away from boxing.

“Playing the violin,” Bugner called it.

“We played it in a way everybody was interested and they still are to this day,” smiled Joe. “Henry and I played the game and he knew how to play it. Trust me.”

It was a shame that, for man, that remained Bugner’s defining night.

A couple of fights later, Bugner was outscored by Jack Bodell in an upset.

“He was very awkward. His timing was completely different to anything I have met in the gymnasium, and it took me 12 rounds to understand what was going on,” Bugner admitted.

“He is young and strong with years of fighting ahead of him, and I am sure he will come again,” Bodell accurately predicted.

Robert Smith, general secretary of the British Boxing Board of Control and himself a good former pro, knew Bugner well. His father, Andy, worked with the heavyweight.

“I was a little boy, four years old, when Joe turned professional with my dad as his trainer and manager in 1967,” recalled Smith. “But I grew up with him around the house and the gym. My dad didn’t have many fighters which allowed him to give each of them plenty of his attention and Joe was no different.

“The rules back then stipulated that anyone challenging for the British title had to be 21 years old and Joe turned 21 only days before he challenged Henry Cooper for the title in 1971. It was a close fight; Joe won the first six or seven rounds and Cooper won the next six or seven because Joe switched off. It was all down to the last round. My dad slapped him before that 15th round and shouted, ‘C’mon Joe, you’ve got to win this round’, which he then did. My dad was later called up on a misconduct charge for slapping him!

“But it was difficult for Joe. He was only 21 and he’d just beaten the national hero. “Thank God there wasn’t social media back then. Some of the abuse he received, and our family received, after that fight was horrendous. I’m not blaming Harry Carpenter for that but his commentary certainly swayed the public’s opinion that Cooper was the victim of a bad decision when he wasn’t – it was a close fight and I believe Joe nicked it. “Colin Hart [the late International Boxing Hall of Fame journalist for The Sun], always a good judge of a fight, believed Joe had won it too.

“But Joe never really got over that. He came from Hungary, too, he was a refugee. “People questioned his ‘Britishness’. Which was a great shame because he was proud of being British and he was proud to be British champion.”

Smith saw the hurt Bugner felt at his very public rejection.

But as time has gone on, Bugner was appreciated as a mainstay of the greatest heavyweight division of all-time, and he more than played his part.

Even with his 1970s rivals long gone, Bugner ploughed on.

After a split decision loss to Lyle in 1977, he did not box for three years and there was just one fight in 1980 before Shavers cut him up in two in 1982 in Dallas.

But he parlayed his Cinderella run in 1986 with victories over Tillis, Bey and Page, all on points over 10 rounds that took him back into both the world rankings and the big Bruno fight, which would be promoter Barry Hearn’s first big foray into boxing.

That was in October 1987. Bugner showed up at a workout with We Promise You Blood, Sweat and Tears on it, but experts rightly predicted that Bruno, 11 years younger, would win.

It was Britain’s richest non-title fight, and the excellent Boxing News editor Harry Mullan pointed out in his preview that even by then Bugner was boxing “after more retirements than Frank Sinatra.”

Mullan was a wonderful writer, but he was hard on Bugner. In his incredibly colorful fight report, he wrote: “Britain’s most over-hyped and overpaid fight in history proved only what was obvious before the event: that boxing in a young man’s game.”

Bugner was 37, very old for the day – not so much today – and Mullan called him “ancient and ill-conditioned.”

You could speculate that there were a couple of near misses with Mike Tyson for Bugner. Certainly, after beating Bugner, Bruno went into his first bout with “Iron” Mike in Las Vegas.

He was also linked to a fight with the returning George Foreman, but even a more mature Bugner didn’t fancy that.

“I wouldn’t even entertain such an idea,” he said. “It would be pathetic. Why would anyone pay money to see us waltzing around the ring.”

Bugner was 44 by then.

Still going in 1996, he lost to world title challenger Scott Welch in Germany – astonishingly 25 years to the day of the Cooper fight.

“He was a lovely man,” said the rugged Brighton heavyweight. “I went to the press conference at the Café Royal [in London] and thought we’d be the same height but he was a giant of a man. He had ginormous hands, and he was a lump. After we fought, we became friends. He came to my house to have dinner on the south coast, Joe Jnr [Bugner’s son] came to train with me after I beat his dad down in London.

“I was a bit surprised to fight him, he was an older guy but he’d been around in the game and he was saying he would hit me with so many jabs I’d be begging for a right. We had some banter and he was a great guy.”

Welch, though, was young and aggressive. As much as he might fondly recall those times now, he did not appreciate Bugner at the time.

“The night before, we were in the same hotel in Berlin and I went into the restaurant and he was in there drinking red wine and he lifted up his glass and nodded, ‘Cheers.’

“I was like, ‘You’re having a laugh.’”

“It was the way the big glass of red that came up and I wanted to smash him to bits.”

Welch laughed, but he had also seen Bugner get rough treatment from the press over the years.

“He beat Cooper,” Welch explained. “Cooper was The Man, he’d dropped Ali, so he was always gonna be the [crowd] favorite and him [Bugner] being a Hungarian-born man… But listen, he was like a film star. He was a massive, good-looking guy. He would beat 90 per cent of them [the best heavyweights] but just didn’t get it over the line.”

Welch battered Bugner in six, and although had six further fights in the following three years, he knew the end was nigh.

“Trust me, I wanted to go out on a high note,” he said. “It didn’t come off, but I had a go and that’s what matters.”

“He was very underrated,” Smith concluded. “Look at his overall body of work, the great fighters that he fought in a truly exceptional era which was surely the best in history.

“And that era was dominated by Americans with British and European fighters just a sidebar. Joe was the only one who really challenged that.

“Somebody asked me the other day how Joe would fare in today’s era and my answer was ‘very well’. But then I thought about it afterwards and perhaps a better question would be: How many of today’s heavyweights would have been able to compete with all the fighters from the seventies that Joe competed with? Not many.”