George Dixon was one of the greatest fighters of all time. He was the first black fighter to win a world boxing championship. He held the bantamweight (1890) and featherweight championships (1891-1897, 1898-1900) winning his first championship at age 20. He fought in 23 world championship bouts (some records indicate 33), the most of any fighter until Joe Louis. Dixon held the Featherweight championship while never weighing beyond 118 pounds. He often fought and defeated men who were natural lightweights. His official record shows 158 bouts, but his record fails to record the actual number of fights he had as many were staged in dance halls and theatres around the country. Dixon’s manager who traveled with him claimed, before his death, that Dixon had over 800 fights sometimes fighting up to 15 times a week (See BD. Vol. 3 p. 7) One issue of the National Police Gazette indicates he had over 1,000. This is a record unparalleled in the history of sports.

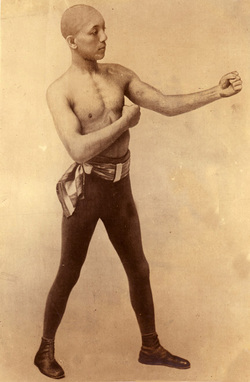

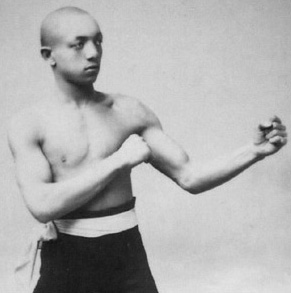

Dixon is considered by many to be the greatest fighter of the 19th century. The newspapers of his day hailed him as "The greatest of them all." In the Jun 27, 1900 Police Gazette there is a photograph stating, “Characteristic fighting pose of the Greatest Pugilist the World ever saw.” Sam Austin, editor of the Gazette once called him “a fighter without a flaw.”

“Little Chocolate” was a superb boxer, who founded the “black school” of pugilism of which Joe Walcott, Jack Johnson, and Joe Gans belonged. Dixon and Walcott shared the same manager in Tom O’Rourke. Gans was a good friend of Dixon and studied under him, while Johnson served as a sparring partner for Walcott in his youth.

Dixon was a fast puncher with an excellent left jab, his best punch being a strong right cross to the chin. He also had a strong left hook. His favorite combination was a left jab to the face, followed by a right to the body and a jab back to the face. His famous fighting method included jabbing, feinting and rushing an opponent to the ropes where he would work the body. He was also known for his defensive ability to dodge, evade, and block his opponent’s blows.

Nat Fleischer, founder of Ring magazine, described him as “a marvel of cleverness, yet he could hit and slug with the best of them. He was fast, tricky, combative, canny, courageous, a master in every respect of the art of self-defense, a great ring general. His left hand was one of the best in the business. His double left to the body has never been equaled. His right was equally good” (B.D. p 6).

Tom O'Rourke described Dixon thusly, "Of all the fighters I have seen none can compare to Dixon in all around fighting ability. What a wonderful left hand! What a double corking punch to the head and body! What a fighting heart and fighting head! What a superb, all around mastery of the manly art he possessed!" (Oct. 1936 Ring Magazine.)

That fighters of this period were already fighting in combination is evident by reading newspaper accounts of Dixon’s battles with the clever Young Griffo. Their June 29, 1894 draw was heralded as “The best battle ever seen at Boston” and featured “very fast in-fighting.” The Police Gazette reported that another of their draws “was a continuous succession of clever feints, rapid exchanges, leads and uppercuts.” “Fast fighting” and “continuous rapid exchanges” sounds remarkably like “sustained combination punching.”

Herbert Goldman noted that, Dixon was an fine boxer who “fought on the balls of his feet.” He had excellent footwork and his agility and fleetness of foot was able to help him in avoiding blows. He could also “spring” into an opponent and had perfect balance.

McCallum wrote that Dixon was “long armed and skinny legged, swift of hand and foot, Little Chocolate boxed like a phantom, slugged like a diminutive longshoreman. He possessed the ideal fighting temperament. Distance meant nothing. He could pick up speed and last all the way” (pp 264-265).

Historian Tracy Callis stated, “Dixon was one of the all-time ring greats; He had fast hands and was quick on his feet like a cat; On offense, he hit with both hands but mostly utilized a long, straight left accompanied by a stiff right; On defense, he guarded himself well; His quickness and ducking ability made him a difficult target to strike.”

Callis also wrote, “Dixon won nearly 90 percent of the draws and losses on his record but due to various reasons he did not get credit for a win; e.g. racial attitude of the times judged him as loser instead of winner (in some bouts), he had to carry opponents in order to get fights, as well as specific rules for a given fight - i.e. the verdict would be draw if no knockout was scored.”

This fact is supported even by the white press of the period. The Sept. 30, 1893 Police Gazette reported “Nearly every time Dixon has been pitted against a champion, no matter whether foreign or native, the majority has named Dixon the loser, probably through prejudice, owing to his color, yet he has won.”

The newspaper record proves that Dixon was robbed of a good number of wins. For example in a bout with a young Abe Attell reported in the Sep. 14, 1901 Police Gazette, the bout was ruled a draw by the Referee. Reading the account however, it is clear that Dixon deserved the decision. Dixon floored Attell in the first round with a right to the chin. In the third round, “They got in a fierce mix, raining in face and body blows one after the other. Dixon seemed to have the better of the going.” Dixon staggered Abe in the eighth. Dixon also finished strongly but the Ref refused to declare Dixon the winner.

In a Featherweight championship match against Cal McCarthy on Mar. 31, 1891 Dixon had to knock out his opponent twice! In the third round little George knocked McCarthy out cold. But the referee, as in a London Prize Ring Rules, allowed McCarthy’s managers to drag him to his corner and revive him. This is strictly against the rules of the Marquis of Queensbury that governed this bout. Dixon’s manager protested but to no avail. Dixon eventually won by knockout in the 22nd round “with a flurry of offensive fighting.” McCarthy couldn’t continue and Dixon won by knockout.

Dixon, because of the color of his skin, often had to fight under unfair and even dangerous circumstances. There were no boxing commissions in those days and the gamblers controlled the sport.

Dixon fought and defeated a lot of great warriors in the ring. He went 70 rounds in his first fight with Cal McCarthy and never hit the canvas once, in fact, in nearly a decade as champion, he never hit the canvas in a regulation match until he lost the title to Terry McGovern. He defeated or drew with such ring legends as Nunc Wallace, Johnny Murphy, Young Griffo, Solly Smith, Pedlar Palmer, Dal Hawkins, future lightweight champion Franke Erne, Abe Attell, and Jem Driscoll.

Perhaps Fleischer described him best saying, “I doubt ever in the history of pugilism has there ever been a fighter of his weight who engaged in so many thrilling battles, most of them finish fights, and yet he was able to remain at the height of his power for so long” (B.D. p 78).

Dixon reigned as a champion for nearly 10 years. He finally lost the title for good to Terry McGovern who stopped him in the eighth round. It was the first time he had been off his feet in a regulation contest. Dixon fought McGovern in a no decision non-title rematch and never again contended for the title. He died penniless in 1909 at the age of 38.

George Dixon was rated as the # 1 all time Bantamweight by both Nat Fleischer and Charley Rose. Cox’s Corner considers him to be the # 2 Bantamweight of all time.

Dixon is considered by many to be the greatest fighter of the 19th century. The newspapers of his day hailed him as "The greatest of them all." In the Jun 27, 1900 Police Gazette there is a photograph stating, “Characteristic fighting pose of the Greatest Pugilist the World ever saw.” Sam Austin, editor of the Gazette once called him “a fighter without a flaw.”

“Little Chocolate” was a superb boxer, who founded the “black school” of pugilism of which Joe Walcott, Jack Johnson, and Joe Gans belonged. Dixon and Walcott shared the same manager in Tom O’Rourke. Gans was a good friend of Dixon and studied under him, while Johnson served as a sparring partner for Walcott in his youth.

Dixon was a fast puncher with an excellent left jab, his best punch being a strong right cross to the chin. He also had a strong left hook. His favorite combination was a left jab to the face, followed by a right to the body and a jab back to the face. His famous fighting method included jabbing, feinting and rushing an opponent to the ropes where he would work the body. He was also known for his defensive ability to dodge, evade, and block his opponent’s blows.

Nat Fleischer, founder of Ring magazine, described him as “a marvel of cleverness, yet he could hit and slug with the best of them. He was fast, tricky, combative, canny, courageous, a master in every respect of the art of self-defense, a great ring general. His left hand was one of the best in the business. His double left to the body has never been equaled. His right was equally good” (B.D. p 6).

Tom O'Rourke described Dixon thusly, "Of all the fighters I have seen none can compare to Dixon in all around fighting ability. What a wonderful left hand! What a double corking punch to the head and body! What a fighting heart and fighting head! What a superb, all around mastery of the manly art he possessed!" (Oct. 1936 Ring Magazine.)

That fighters of this period were already fighting in combination is evident by reading newspaper accounts of Dixon’s battles with the clever Young Griffo. Their June 29, 1894 draw was heralded as “The best battle ever seen at Boston” and featured “very fast in-fighting.” The Police Gazette reported that another of their draws “was a continuous succession of clever feints, rapid exchanges, leads and uppercuts.” “Fast fighting” and “continuous rapid exchanges” sounds remarkably like “sustained combination punching.”

Herbert Goldman noted that, Dixon was an fine boxer who “fought on the balls of his feet.” He had excellent footwork and his agility and fleetness of foot was able to help him in avoiding blows. He could also “spring” into an opponent and had perfect balance.

McCallum wrote that Dixon was “long armed and skinny legged, swift of hand and foot, Little Chocolate boxed like a phantom, slugged like a diminutive longshoreman. He possessed the ideal fighting temperament. Distance meant nothing. He could pick up speed and last all the way” (pp 264-265).

Historian Tracy Callis stated, “Dixon was one of the all-time ring greats; He had fast hands and was quick on his feet like a cat; On offense, he hit with both hands but mostly utilized a long, straight left accompanied by a stiff right; On defense, he guarded himself well; His quickness and ducking ability made him a difficult target to strike.”

Callis also wrote, “Dixon won nearly 90 percent of the draws and losses on his record but due to various reasons he did not get credit for a win; e.g. racial attitude of the times judged him as loser instead of winner (in some bouts), he had to carry opponents in order to get fights, as well as specific rules for a given fight - i.e. the verdict would be draw if no knockout was scored.”

This fact is supported even by the white press of the period. The Sept. 30, 1893 Police Gazette reported “Nearly every time Dixon has been pitted against a champion, no matter whether foreign or native, the majority has named Dixon the loser, probably through prejudice, owing to his color, yet he has won.”

The newspaper record proves that Dixon was robbed of a good number of wins. For example in a bout with a young Abe Attell reported in the Sep. 14, 1901 Police Gazette, the bout was ruled a draw by the Referee. Reading the account however, it is clear that Dixon deserved the decision. Dixon floored Attell in the first round with a right to the chin. In the third round, “They got in a fierce mix, raining in face and body blows one after the other. Dixon seemed to have the better of the going.” Dixon staggered Abe in the eighth. Dixon also finished strongly but the Ref refused to declare Dixon the winner.

In a Featherweight championship match against Cal McCarthy on Mar. 31, 1891 Dixon had to knock out his opponent twice! In the third round little George knocked McCarthy out cold. But the referee, as in a London Prize Ring Rules, allowed McCarthy’s managers to drag him to his corner and revive him. This is strictly against the rules of the Marquis of Queensbury that governed this bout. Dixon’s manager protested but to no avail. Dixon eventually won by knockout in the 22nd round “with a flurry of offensive fighting.” McCarthy couldn’t continue and Dixon won by knockout.

Dixon, because of the color of his skin, often had to fight under unfair and even dangerous circumstances. There were no boxing commissions in those days and the gamblers controlled the sport.

Dixon fought and defeated a lot of great warriors in the ring. He went 70 rounds in his first fight with Cal McCarthy and never hit the canvas once, in fact, in nearly a decade as champion, he never hit the canvas in a regulation match until he lost the title to Terry McGovern. He defeated or drew with such ring legends as Nunc Wallace, Johnny Murphy, Young Griffo, Solly Smith, Pedlar Palmer, Dal Hawkins, future lightweight champion Franke Erne, Abe Attell, and Jem Driscoll.

Perhaps Fleischer described him best saying, “I doubt ever in the history of pugilism has there ever been a fighter of his weight who engaged in so many thrilling battles, most of them finish fights, and yet he was able to remain at the height of his power for so long” (B.D. p 78).

Dixon reigned as a champion for nearly 10 years. He finally lost the title for good to Terry McGovern who stopped him in the eighth round. It was the first time he had been off his feet in a regulation contest. Dixon fought McGovern in a no decision non-title rematch and never again contended for the title. He died penniless in 1909 at the age of 38.

George Dixon was rated as the # 1 all time Bantamweight by both Nat Fleischer and Charley Rose. Cox’s Corner considers him to be the # 2 Bantamweight of all time.

Comment