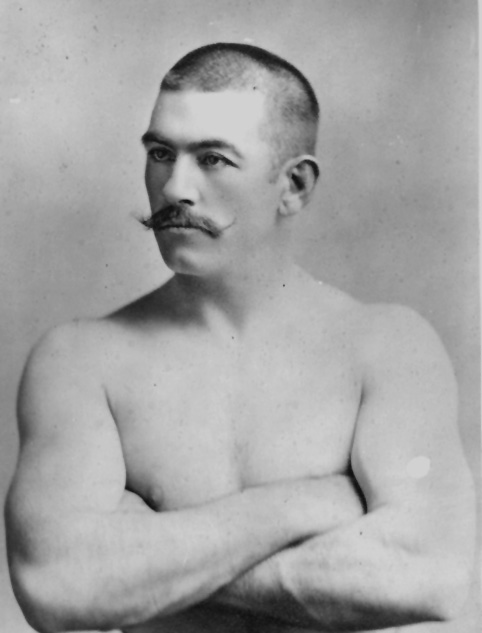

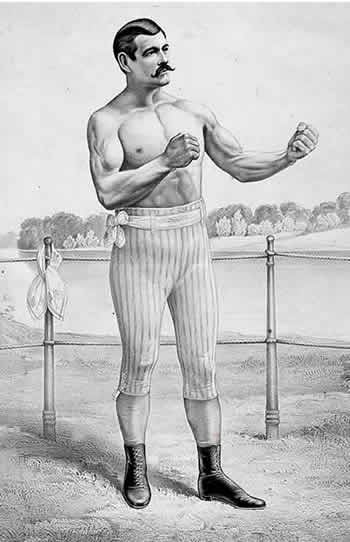

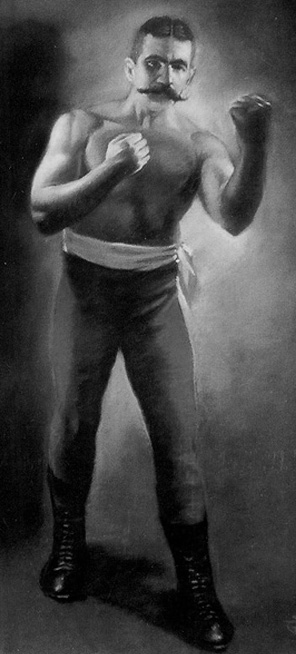

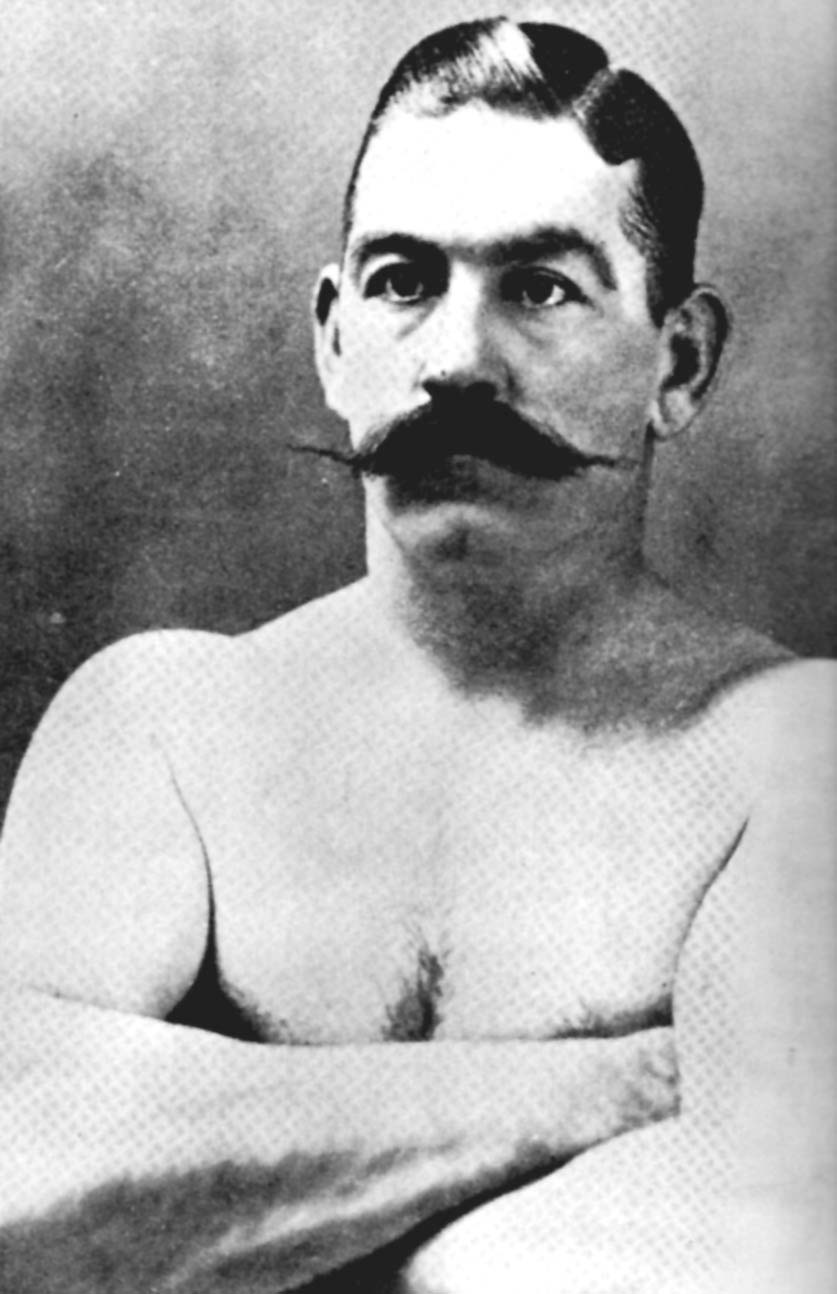

John L. Sulivan (October 12, 1858 – February 2, 1918)

When people used to say “shake the hand which shook the hand which shook the hand of The Great John L.” it really meant something. During his reign as heavyweight champion of the world from 1882-1892, and for many years thereafter, John L. Sullivan was iconic, larger than life, a touchstone embodying excellence in a nation just beginning to manifest its destiny.

But nowadays no one knows much about John L.

John L. Sullivan was a pivotal figure in the history of the fight game. He started fighting while boxing was illegal. He was the last bare-knuckle heavyweight champ. He was the first gloved heavyweight champ. He was America’s first sports celebrity.

John Lawrence Sullivan was born in Roxbury, Massachusetts, a suburb of Boston, on October 15, 1858 to proud Irish roots. His father Michael was from Tralee in County Kerry and his mother hailed from Athlone in County Roscommon. Michael Sullivan was a tough guy always itching for a fight, but he was, alas, a short fellow, only 5'3" tall, whereas John L.’s mother, at 5'10” and 190 pounds, was built like a battleship.

John L. Sullivan took after his mum and dad.

To bestow honor on the Sullivan name, and at his mother’s insistence, John L. decided to become a priest. He gave it his best shot, but his best shot was not good enough. The priesthood was not for John L, nor was being a hod carrier, assistant plumber or tinsmith.

Like any Irish lad with a few quid in his pocket, Sullivan liked drinking, carousing and fighting, followed by more drinking, carousing and fighting. John L. would stride into bars and proclaim: “I can lick any man in the house.” Only masochists in their cups begged to differ.

John L. Sullivan had prodigious strength and prodigious appetites and swaggered and blustered with the best of them. But he wasn’t just a thug. He was also athletic. Sullivan played semi-pro baseball in Boston and was offered a contract by the Cincinnati Red Stockings of the nascent major league to play pro ball, but the directionless John L., with no other prospects in sight, turned the big leagues down flat.

Sullivan began a fledgling career as amateur fighter giving boxing, wrestling and weightlifting exhibitions. He was a bit of a nobody on the fringe, a roustabout with power, a hard-nosed, hardheaded, hard-fisted Irishman still finding his way in the world.

Fate intervened in the life of The Great John L. at Boston’s Dudley Opera House during an evening of light entertainment in 1877. The stage show featured a sparring session where a heavyweight boxer named Tom Scannel challenged all comers in the audience, daring anyone to last three rounds. Most of the men that rose from the crowd were shills who were in on the ruse, which was poor training to fight a young unknown named John L. Sullivan.

At the urging of the audience, Sullivan stood, removed his jacket and tie, rolled up his sleeves, and strode up the steps up to the stage. According to legend, John L. walked over to Scannel for a collegial handshake. Scannel reeled back and sucker-punched Sullivan with a left to the cheek. Sullivan countered with a right to Scannel’s jaw, knocking the showman into the orchestra pit. According to Sullivan, “I didn’t know the first thing about boxing then, but I went at him for all I was worth and licked him quick. It wasn’t much of a fight, and I done him up in about two minutes.”

John L. had four fights in 1878, including a bout with John “Cocky” Woods. Woods was no slouch, but Sullivan stopped him with a straight right, scoring a fifth round TKO.

In 1880 Sullivan fought and defeated Joe Goss, the former American champ, in three rounds. John L. had two more fights that year, kayos over George Rooke and John Donaldson in Boston and Cincinnati.

That same year Sullivan boxed an exhibition with the noted fitness freak and boxing trainer Professor Mike Donovan. Donovan wrote that John L. knew nothing about boxing, “but he was the most savage fighter and hardest hitter that ever lived.” Sullivan “scorned to study the methods or copy the style of anyone. He had a natural genius for fighting. He never stepped back.” Donovan also described what it was like being hit by Sullivan’s punches: “It was like being kicked in the head by a runaway horse.”

“When I started out boxing,” Sullivan wrote some years later, “I felt within myself, as I do now, that I could knock out any man living.”

John L. Sullivan had seven fights in 1881, including a bare-knuckle barnburner against a New York thug and enforcer named John Flood, aka The Bull’s Head Terror, on a barge anchored in the Hudson River near Yonkers. Sullivan knocked Flood down eight times en route to an eighth round knockout.

Sullivan kept fighting. Sullivan kept winning. He had eight fights in 1882, all of them with gloves, except for his title fight with the American bare-knuckle champion Paddy Ryan on February 7, 1882 in Mississippi City, Mississippi. Sullivan controlled the action and floored Ryan with a right in the ninth. The Great John L. Sullivan was heavyweight champion of the world.

The champ had seven fights in ‘83, ten in ‘84, four in 1885, including a bout on August 29 in Cincinnati against Dominick McCaffrey for the vacant Marquis of Queensberry heavyweight title. It took Sullivan six rounds to finish McCaffrey.

The Great John L. had four fights in the next two years. Then he met Charlie Mitchell in Chantilly, France on March 18, 1888 on the rain-soaked estate of Baron Rothschild. The two men fought without gloves, under the provisions of the London Prize Ring Rules, to a thirty-nine round draw. Sullivan was still the champ.

On July 8, 1889, in Richburg, Mississippi, Sullivan met Jake Kilrain in the last bare-knuckle heavyweight championship fight in history. Sullivan dropped thirty-five pounds to get in shape for the bout - and it’s a good thing that he did. After seventy-five rounds, in a fight that lasted two hours and sixteen minutes, and with John L. taunting “You’re a champion, eh? Champion of what?” Kilrain could take no more. Sullivan retained his crown.

The next day the New York Times, as pro boxing then as it is today, ran a headline which blared: THE BIGGER BRUTE WON. Sullivan countered by saying, “if Kilrain had stood up and fought like a man I think I could have whipped him in about eight rounds.”

John L. Sullivan was now more famous than fame itself. The man who used to boast “I can lick any man in the house” now crowed “I can lick any son of a ***** in the world!” Everything he said, everything he did, was fodder for a hungry public. They could not get enough of The Great John L. And Sullivan played it to the hilt. He drank. He gambled. He whored. John L. also took a three-year hiatus from fighting. Instead of defending his title, he defended low art by touring in a play called Honest Hearts and Willing Hands, a tearjerker at which some jerks shed tears.

“I don’t want to sound egotistical,” Sullivan said at the time. “But I hope someday to be as great an actor as Booth . . . I’ve just begun this business now and of course I’m not up on all points. But they’ll come along, all right . . . None of the great actors had to study much.”

Sullivan was mistaken. Actors study. As do prizefighters. And one of the game’s great students was an athletic young bank clerk from San Francisco named James J. Corbett.

Sullivan and Corbett’s first meeting was at the Grand Opera House in SF while the heavyweight champion was on his theatrical tour. Corbett answered a public challenge and the men engaged in four polite rounds of gloved sparring in eveningwear before a select audience. It was, needless to say, more of a clown show than a fight.

Corbett had been challenging Sullivan for years to no avail. It was like a fly pestering a colossus at the stroke of midnight.

Sullivan agreed to meet Corbett on September 7, 1892 in New Orleans and it was a coup in the squared circle. The men wore gloves, in accordance with the Queensberry Rules, and which would forever be the custom, and Jim Corbett toppled a legend. John L.’s lumbering charges and roundhouse blows were ready-made for Gentleman Jim. In the third round Corbett broke Sullivan’s nose, which bled for the rest of the fight. Corbett jabbed and danced, jabbed and glided, feinting, moving, scoring combinations to Sullivan’s head and body for round after round after round.

In the twenty-first round Corbett landed a right which dropped Sullivan. He staggered to his feet and Corbett landed a perfect one-two combination. John L. Sullivan sank to his knees. He fought to beat the count, but it was not to be. The Great John L. was great no more. The new heavyweight champion of the world was Gentleman Jim Corbett.

That was John L. Sullivan’s last hurrah as a pro. He quit the game with a record of 50-1-4 (35 KOs). He resumed his acting career, gave occasional boxing demonstrations, had a conversion and stopped drinking. The Great John L. used his fame and notoriety to become a lecturer on the temperance circuit. He spoke to prim and proper ladies, teetotalers and dry drunks about the evils of demon rum.

Sullivan retired to his farm in Massachusetts, penniless but content, and died on February 2, 1918.

The lessons John L. learned in life are summed up in his memoirs and are as applicable today as they were a hundred years ago: “It is very much better for the young, as well as the old, to possess the knowledge of the manly art of self-defense than it is to have them resort to knives and guns.”

But nowadays no one knows much about John L.

John L. Sullivan was a pivotal figure in the history of the fight game. He started fighting while boxing was illegal. He was the last bare-knuckle heavyweight champ. He was the first gloved heavyweight champ. He was America’s first sports celebrity.

John Lawrence Sullivan was born in Roxbury, Massachusetts, a suburb of Boston, on October 15, 1858 to proud Irish roots. His father Michael was from Tralee in County Kerry and his mother hailed from Athlone in County Roscommon. Michael Sullivan was a tough guy always itching for a fight, but he was, alas, a short fellow, only 5'3" tall, whereas John L.’s mother, at 5'10” and 190 pounds, was built like a battleship.

John L. Sullivan took after his mum and dad.

To bestow honor on the Sullivan name, and at his mother’s insistence, John L. decided to become a priest. He gave it his best shot, but his best shot was not good enough. The priesthood was not for John L, nor was being a hod carrier, assistant plumber or tinsmith.

Like any Irish lad with a few quid in his pocket, Sullivan liked drinking, carousing and fighting, followed by more drinking, carousing and fighting. John L. would stride into bars and proclaim: “I can lick any man in the house.” Only masochists in their cups begged to differ.

John L. Sullivan had prodigious strength and prodigious appetites and swaggered and blustered with the best of them. But he wasn’t just a thug. He was also athletic. Sullivan played semi-pro baseball in Boston and was offered a contract by the Cincinnati Red Stockings of the nascent major league to play pro ball, but the directionless John L., with no other prospects in sight, turned the big leagues down flat.

Sullivan began a fledgling career as amateur fighter giving boxing, wrestling and weightlifting exhibitions. He was a bit of a nobody on the fringe, a roustabout with power, a hard-nosed, hardheaded, hard-fisted Irishman still finding his way in the world.

Fate intervened in the life of The Great John L. at Boston’s Dudley Opera House during an evening of light entertainment in 1877. The stage show featured a sparring session where a heavyweight boxer named Tom Scannel challenged all comers in the audience, daring anyone to last three rounds. Most of the men that rose from the crowd were shills who were in on the ruse, which was poor training to fight a young unknown named John L. Sullivan.

At the urging of the audience, Sullivan stood, removed his jacket and tie, rolled up his sleeves, and strode up the steps up to the stage. According to legend, John L. walked over to Scannel for a collegial handshake. Scannel reeled back and sucker-punched Sullivan with a left to the cheek. Sullivan countered with a right to Scannel’s jaw, knocking the showman into the orchestra pit. According to Sullivan, “I didn’t know the first thing about boxing then, but I went at him for all I was worth and licked him quick. It wasn’t much of a fight, and I done him up in about two minutes.”

John L. had four fights in 1878, including a bout with John “Cocky” Woods. Woods was no slouch, but Sullivan stopped him with a straight right, scoring a fifth round TKO.

In 1880 Sullivan fought and defeated Joe Goss, the former American champ, in three rounds. John L. had two more fights that year, kayos over George Rooke and John Donaldson in Boston and Cincinnati.

That same year Sullivan boxed an exhibition with the noted fitness freak and boxing trainer Professor Mike Donovan. Donovan wrote that John L. knew nothing about boxing, “but he was the most savage fighter and hardest hitter that ever lived.” Sullivan “scorned to study the methods or copy the style of anyone. He had a natural genius for fighting. He never stepped back.” Donovan also described what it was like being hit by Sullivan’s punches: “It was like being kicked in the head by a runaway horse.”

“When I started out boxing,” Sullivan wrote some years later, “I felt within myself, as I do now, that I could knock out any man living.”

John L. Sullivan had seven fights in 1881, including a bare-knuckle barnburner against a New York thug and enforcer named John Flood, aka The Bull’s Head Terror, on a barge anchored in the Hudson River near Yonkers. Sullivan knocked Flood down eight times en route to an eighth round knockout.

Sullivan kept fighting. Sullivan kept winning. He had eight fights in 1882, all of them with gloves, except for his title fight with the American bare-knuckle champion Paddy Ryan on February 7, 1882 in Mississippi City, Mississippi. Sullivan controlled the action and floored Ryan with a right in the ninth. The Great John L. Sullivan was heavyweight champion of the world.

The champ had seven fights in ‘83, ten in ‘84, four in 1885, including a bout on August 29 in Cincinnati against Dominick McCaffrey for the vacant Marquis of Queensberry heavyweight title. It took Sullivan six rounds to finish McCaffrey.

The Great John L. had four fights in the next two years. Then he met Charlie Mitchell in Chantilly, France on March 18, 1888 on the rain-soaked estate of Baron Rothschild. The two men fought without gloves, under the provisions of the London Prize Ring Rules, to a thirty-nine round draw. Sullivan was still the champ.

On July 8, 1889, in Richburg, Mississippi, Sullivan met Jake Kilrain in the last bare-knuckle heavyweight championship fight in history. Sullivan dropped thirty-five pounds to get in shape for the bout - and it’s a good thing that he did. After seventy-five rounds, in a fight that lasted two hours and sixteen minutes, and with John L. taunting “You’re a champion, eh? Champion of what?” Kilrain could take no more. Sullivan retained his crown.

The next day the New York Times, as pro boxing then as it is today, ran a headline which blared: THE BIGGER BRUTE WON. Sullivan countered by saying, “if Kilrain had stood up and fought like a man I think I could have whipped him in about eight rounds.”

John L. Sullivan was now more famous than fame itself. The man who used to boast “I can lick any man in the house” now crowed “I can lick any son of a ***** in the world!” Everything he said, everything he did, was fodder for a hungry public. They could not get enough of The Great John L. And Sullivan played it to the hilt. He drank. He gambled. He whored. John L. also took a three-year hiatus from fighting. Instead of defending his title, he defended low art by touring in a play called Honest Hearts and Willing Hands, a tearjerker at which some jerks shed tears.

“I don’t want to sound egotistical,” Sullivan said at the time. “But I hope someday to be as great an actor as Booth . . . I’ve just begun this business now and of course I’m not up on all points. But they’ll come along, all right . . . None of the great actors had to study much.”

Sullivan was mistaken. Actors study. As do prizefighters. And one of the game’s great students was an athletic young bank clerk from San Francisco named James J. Corbett.

Sullivan and Corbett’s first meeting was at the Grand Opera House in SF while the heavyweight champion was on his theatrical tour. Corbett answered a public challenge and the men engaged in four polite rounds of gloved sparring in eveningwear before a select audience. It was, needless to say, more of a clown show than a fight.

Corbett had been challenging Sullivan for years to no avail. It was like a fly pestering a colossus at the stroke of midnight.

Sullivan agreed to meet Corbett on September 7, 1892 in New Orleans and it was a coup in the squared circle. The men wore gloves, in accordance with the Queensberry Rules, and which would forever be the custom, and Jim Corbett toppled a legend. John L.’s lumbering charges and roundhouse blows were ready-made for Gentleman Jim. In the third round Corbett broke Sullivan’s nose, which bled for the rest of the fight. Corbett jabbed and danced, jabbed and glided, feinting, moving, scoring combinations to Sullivan’s head and body for round after round after round.

In the twenty-first round Corbett landed a right which dropped Sullivan. He staggered to his feet and Corbett landed a perfect one-two combination. John L. Sullivan sank to his knees. He fought to beat the count, but it was not to be. The Great John L. was great no more. The new heavyweight champion of the world was Gentleman Jim Corbett.

That was John L. Sullivan’s last hurrah as a pro. He quit the game with a record of 50-1-4 (35 KOs). He resumed his acting career, gave occasional boxing demonstrations, had a conversion and stopped drinking. The Great John L. used his fame and notoriety to become a lecturer on the temperance circuit. He spoke to prim and proper ladies, teetotalers and dry drunks about the evils of demon rum.

Sullivan retired to his farm in Massachusetts, penniless but content, and died on February 2, 1918.

The lessons John L. learned in life are summed up in his memoirs and are as applicable today as they were a hundred years ago: “It is very much better for the young, as well as the old, to possess the knowledge of the manly art of self-defense than it is to have them resort to knives and guns.”

Comment