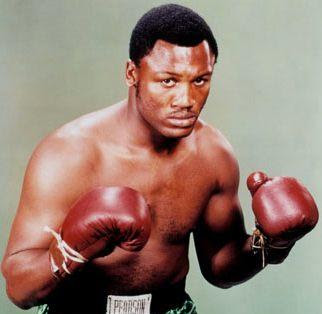

When Joe was born, his father named him Billy, after his rugged old Ford that never let him down on the dark back roads he raced through. “He gonna be my left arm,” Rubin said of the baby. By day, Rubin was an overseer on the Bellamy farm, at night he cooked up “white lightning” that he sold for seven dollars a gallon. Turned age seven, Joe began helping him with late-night liquor deliveries. “I was never little, or played little,” he would say. “I ran with my father.” In the early fifties, Rubin bought a small television, and the high point of Joe’s week was watching the weekly fights with his father and uncles. No matter who was fighting, the talk always ended up with the name Joe Louis. His father respected Louis so much that the name blazed in Joe’s head. To show his father that he could be Louis, too, he put a bag on a tree limb filled with bricks at the center, rags, and corncobs, and he pounded the bag day after day with an audience of his two mules, Buck and Jenny, until his hands were bloody

Joe Frazier: In the beginning 1-2

The Heavyweights

A series of threads about Frazier, Ali, Patterson and Tyson

The stern Dolly didn’t like it much, and allowed him only an hour with the bag. She tried to curb his father’s influence by taking him to church, where his main function was to hold on to his mother’s hysterical friend who would be so in rapture that she might shake herself

into injury. A dedicated truant in school, Joe was soon working with his father on the Bellamy land, and he lay awake plotting how he could make his way elsewhere, away from a place where doctors treated whites first, where a white store had a parrot that sang: “******s teefing, ******s teefing.” Teefing meaning stealing. It was at the Bellamy farm where the kid came to the aid of a

smaller black boy who was being beaten by one of the Bellamys out in the field. He told the other workers that “it wasn’t right to strap the kid,” and the word got back. The man approached Joe in a rage, saying: “Tell you what, ******, I want you off this place before I take this belt off again.” Joe told him to keep the belt for his pants, “’cause you’re not usin’ no belt on me!” He saw the future clearly, he had to get out, and Dolly, worried, told him: “Son, if you can’t get along with

white folks, then leave home’ cause I don’t want you gettin’ hurt.” Not even “the dog” (the Greyhound bus) stopped in Beaufort. Soon after, the Greyhound started making stops there, and in 1959 he took “the first dog North.” He was only 15, with not one asset to recommend

a decent continuity of life. He went to live with brother Tommy in Brooklyn, where for two

years he looked for any kind of work, lay around, and then desperate that he couldn’t pay his own way he began to steal old cars with a friend and sell them for fifty dollars to a junkyard. Besides, there was his girl, Florence, by now pregnant. He decided to go and live with relatives

in Philadelphia. He had blown up to 220 pounds, felt disgusted; what had happened to the kid who had attacked the bag of corncobs? He talked his way into a job at Cross Brothers slaughterhouse. He swept the floor, hosed blood down, threw the waste down a chute. Sometimes, he’d cart huge slabs of beef into the freezer, where he practiced combinations, his mouth streaming vapor. Sylvester Stallone lifted that from him for Rocky, and took some more, Joe’s later habit of doing roadwork

up the famous museum steps, only there wasn’t any victorious soundtrack then. Fed up with the size of his thighs, he went to the PAL gym to lose weight. “The more I got whipped on,” he said, “and it was often, the more I wanted it.” Duke Dugent, head of the gym, saw a serious kid who could whack if ever taught, and he told Durham about him. “Does he have any balls?” he asked. “More than I’ve seen,” Dugent told him. Under Durham, Joe became a top amateur, but he was robbed of a decision in an Olympic trial against Buster Mathis, a three-hundred-pound ballroom dancer in the ring. Joe was down, wanted to quit. “You a baby, that it,” Durham said. “Go on, then, butcher them cows the rest of your life.” He was still at Cross, often slicing his fingers with knives; his hands were showing more stitches than a baseball glove. Durham talked him into being a sparring partner for Mathis. Buster was lazy, unmotivated, and the coaches saw it. Stick around, they told Joe. If this guy catches a cold, “you’re in.” Buster came up with an injured knuckle. Joe went on to win the gold

medal at the Tokyo Olympics in 1964. Frazier was in bad shape economically when he returned. He was

now married to Florence and had two children. Local sportswriter Stan Hochman heard of his problem, and soon gifts and money began showing up, one of them a golf bag filled to the top with five- and

one-dollar bills from a collection that had been made on the street. How now to make his big move as a pro? Durham went to black business leaders. They turned him down cold, saying that Joe was too

small, his arms too short for a heavyweight. “**** ’em,” Yank said, “we’ll do it alone.” Back to Cross and more stitches; one day a bull escaped inside and headed right for Joe; it was shot dead. With all the blood, the smell, the long hours, cut off from the gym in a full-time

way, he began to feel like one of those steers, shackled and hoisted, just before the rabbi slit its throat. He told Florence: “Man, I gotta get outta there.”

next

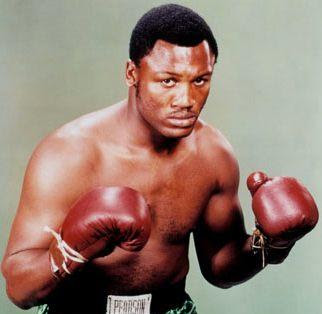

Joe Frazer: In the beginning 2-2

Joe Frazier: In the beginning 1-2

The Heavyweights

A series of threads about Frazier, Ali, Patterson and Tyson

The stern Dolly didn’t like it much, and allowed him only an hour with the bag. She tried to curb his father’s influence by taking him to church, where his main function was to hold on to his mother’s hysterical friend who would be so in rapture that she might shake herself

into injury. A dedicated truant in school, Joe was soon working with his father on the Bellamy land, and he lay awake plotting how he could make his way elsewhere, away from a place where doctors treated whites first, where a white store had a parrot that sang: “******s teefing, ******s teefing.” Teefing meaning stealing. It was at the Bellamy farm where the kid came to the aid of a

smaller black boy who was being beaten by one of the Bellamys out in the field. He told the other workers that “it wasn’t right to strap the kid,” and the word got back. The man approached Joe in a rage, saying: “Tell you what, ******, I want you off this place before I take this belt off again.” Joe told him to keep the belt for his pants, “’cause you’re not usin’ no belt on me!” He saw the future clearly, he had to get out, and Dolly, worried, told him: “Son, if you can’t get along with

white folks, then leave home’ cause I don’t want you gettin’ hurt.” Not even “the dog” (the Greyhound bus) stopped in Beaufort. Soon after, the Greyhound started making stops there, and in 1959 he took “the first dog North.” He was only 15, with not one asset to recommend

a decent continuity of life. He went to live with brother Tommy in Brooklyn, where for two

years he looked for any kind of work, lay around, and then desperate that he couldn’t pay his own way he began to steal old cars with a friend and sell them for fifty dollars to a junkyard. Besides, there was his girl, Florence, by now pregnant. He decided to go and live with relatives

in Philadelphia. He had blown up to 220 pounds, felt disgusted; what had happened to the kid who had attacked the bag of corncobs? He talked his way into a job at Cross Brothers slaughterhouse. He swept the floor, hosed blood down, threw the waste down a chute. Sometimes, he’d cart huge slabs of beef into the freezer, where he practiced combinations, his mouth streaming vapor. Sylvester Stallone lifted that from him for Rocky, and took some more, Joe’s later habit of doing roadwork

up the famous museum steps, only there wasn’t any victorious soundtrack then. Fed up with the size of his thighs, he went to the PAL gym to lose weight. “The more I got whipped on,” he said, “and it was often, the more I wanted it.” Duke Dugent, head of the gym, saw a serious kid who could whack if ever taught, and he told Durham about him. “Does he have any balls?” he asked. “More than I’ve seen,” Dugent told him. Under Durham, Joe became a top amateur, but he was robbed of a decision in an Olympic trial against Buster Mathis, a three-hundred-pound ballroom dancer in the ring. Joe was down, wanted to quit. “You a baby, that it,” Durham said. “Go on, then, butcher them cows the rest of your life.” He was still at Cross, often slicing his fingers with knives; his hands were showing more stitches than a baseball glove. Durham talked him into being a sparring partner for Mathis. Buster was lazy, unmotivated, and the coaches saw it. Stick around, they told Joe. If this guy catches a cold, “you’re in.” Buster came up with an injured knuckle. Joe went on to win the gold

medal at the Tokyo Olympics in 1964. Frazier was in bad shape economically when he returned. He was

now married to Florence and had two children. Local sportswriter Stan Hochman heard of his problem, and soon gifts and money began showing up, one of them a golf bag filled to the top with five- and

one-dollar bills from a collection that had been made on the street. How now to make his big move as a pro? Durham went to black business leaders. They turned him down cold, saying that Joe was too

small, his arms too short for a heavyweight. “**** ’em,” Yank said, “we’ll do it alone.” Back to Cross and more stitches; one day a bull escaped inside and headed right for Joe; it was shot dead. With all the blood, the smell, the long hours, cut off from the gym in a full-time

way, he began to feel like one of those steers, shackled and hoisted, just before the rabbi slit its throat. He told Florence: “Man, I gotta get outta there.”

next

Joe Frazer: In the beginning 2-2

Comment